Gezi Protests as Festival of Revolution

Magdalena Sliwinska

June 2014

Georges Perec underlined that the everyday does not achieve any real existence until it reaches the extraordinariness of sort: until something spectacular, such as scandal, danger, tidal waves, fires or explosions happen (1977: 206). Media and politics revolve around these exceptional moments in life, the moments that break from the ordinary causing for a sort of festivity. For Henri Lefebvre the everyday was merely a point of reference, a repetitious part of life, which could bring changes only with la fête (the festival) – the moment that could bring the end of passivity and resignation (Highmore: 119). Such moments of change, which Lefebvre marks as the ‘end of history’ occur during the times of revolution: inThe Style of Commune, Lefebvre refers to the inception of the Paris Commune, which briefly governed France in 1871 and brought the aforementioned changes (1965: 188). Nowadays, with the move from printed media to social media people have created a new space for themselves: a virtual space where they can freely exchange views on matters of common good and challenge the hierarchies of the ruling classes (Abbott, 2012: 334). This new space continually comes to existence as a network and aggregates people in one physical place that could take the character of Lefebvre’s festival or Mikhail Bakhtin’s carnival. All these can happen not only in suppressed countries, where the freedoms are restricted, but also in democratic countries. By comparing to the American-founded movement of #Occupy and analyzing the socio-political causes of the movements’ emergence, this paper will focus on the Gezi protests as the festival of revolution.

According to Freedom House Ranking, Turkey has a partly free status, which places the country right next to Ukraine, Egypt and Libya when it comes to civil liberties and political rights. While in the beginning of 2000s Turkey was much more restrictive towards its citizens, the slight enhancement of the people’s rights came between years of 2005-2012, only to drop again in 2013, following a number of religion-motivated restrictions (e.g. self-censoring of academicians, prosecuting military members [Freedom House Ranking, 2014]). The ruling party named Justice and Development (AKP), which is in power for more than a decade now, has improved the economic development of the country while also strengthening the religious foundations of its citizens. The controversial decisions that the AKP has made touched upon the subject of alcohol consumption, calling for a ban on abortion, arresting people for blasphemy, limiting the freedom of speech, changing the school system, removing the T.C. (The Republic of Turkey) in front of the bank of Ziraat’s name (as in attempt to change the regime), and many others. As Althusser said, the ideology is important to keep an individual as a believer of something (duty, justice, God), otherwise it is difficult to make people internalize the material practices of the state apparatuses (1990: 159). It is the ideology then that gives knowledge to people and recognition of themselves (309). While trying to look at any particular reason for Gezi protests, one must look, thus, for the reason of the state’s ideology’s failure. Turkey, as a secular country, has found its citizens at the time of the polarization of society between these who support the reforms of the leading party and those, who, for various reasons, disagree with them. Clearly then, the practices that the government imposes taking away people’s liberties, irreversibly make them reject the new practices of the state.

The Gezi protests started at the end of May 2013 and spread from the park in the center of Istanbul to other cities within the country. What was supposed to be a peaceful sit-in of environmental activists, ended up in a brutal police attack, which caused for tumult within the nation. The behavior of Turkey’s Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who not only ignored the protestors, but also referred to them in many offensive ways, following threats and aggression, caused with his attitude much more animosity towards him among his opponents. The lack of mediation in peacekeeping on the government’s side is surprising due to the fact that the country’s representatives tend to position themselves as democrats rather than as authoritarians. There is perversity in recent statement of the Turkish Prime Minister saying that for male and female students to live under the same roof is “against our [Turkish] democratic character” (Hürriyet Daily News, 2013), proving that the Turkish government has quite a different (and perhaps unique) view on what democracy is.

Ben Highmore argued that Lefebvre saw the everyday functioning with the increased homogeneity (happening via standardization of work and commodification) and deepening of social differences with the fragmentation of time, space and knowledge (119). Mentioned above, la fête would bring a change to this fixed order. It would be a part of everyday and yet it would reconfigure it radically (122). What would characterize this festival, on one hand, is the “merry-making” – the entertaining part of it where the community gets together and celebrates while dancing, drinking and eating without any rules and limits. On the other hand, however, the festival would also need to contain drama: “a festival lived by the people and for the people, a colossal festival accompanied by the voluntary sacrifice of the principal actor in the course of his defeat, tragedy” (Lefevbre, 189).

The protests such as #Occupy movement can be seen in the categories of such festival. Jeffrey Juris wrote in his article about the incidents that happened in 2011 in the USA (related to the economic disparities in America as well as in other parts of the world) that the occupiers “succeeded by following a classic civil disobedience strategy: placing their bodies where they were not supposed to be” (268). People got together as if in an effervescent moment of reality suspension and established camps in which they lived as if in Paris Commune of 1871 so well depicted by Lefevbre. They were feeding themselves there, marching together, making performances, workshops; they even created their own housing, media and newspaper (2012: 264). There were a variety of people who joined the protests: they were neither liberal nor conservative; on the contrary, many of them were considered apolitical until the protests, and yet they managed to aggregate themselves together for the common purpose. Juris characterized these different ways of protesting that varied from diverse protest performances as “sit-ins, carnivalesque street parties and acts of militant confrontation with the police” (267).

For Lefebvre these festivals were not a vision of Romantic revolution: he sought them rather as a chance for a division of cultural labor between folk-culture and urban capitalism (Grindon: 213). It was a sort of learning experience, which one can understand in #Occupy: through the existence of workshops and purpose of exchanging ideas people had a chance to understand not only the socio-political conditions they live in but also each other.

Perhaps yet what this revolutionary festival reminds is rather the carnival. Discussed by Bakhtin much, the carnival was more than a festival, it was a counter-model of culture for the oppressed, an overthrow of oppressive social structures by the ecstatic collectivity who wished for a sort of utopia that would take them far away from the reality of the everyday life (Highmore, 123). Many talk of the Bakhtin’s carnival in a very limited sense focusing merely on what he emphasized as freeing of the physiological needs during such event. Despite this bodily-liberation, the carnival carries with itself also a mode of resistance, mocking those in power as the instruments of power itself – religion and the government institutions (Thompson, 116). Parodying the rulers and realizing the physiological aspects of life such as death and decay were to help people not to be contained by oppressive authority.

Gezi protests shared much with #Occupy movement when it comes to organization and its execution. Although the motives for each were different, they both stemmed from the success that Arab Spring managed to reach just via social media. Both had a festival-like construction trying to create a commune of people who could share the ideas and help them become more spread. There was much of merry-making during the 2013 Turkey protests: in various places of the city people were meeting, drinking and dancing together. The rules such as public prohibition of alcohol consumption became suspended and the people gathered around squares and parks to celebrate their newly found comradeship. Social media helped thus to achieve a new identity that would accommodate these expanding coalitions of groups by reaching the state of the carnival (Bennett, 149). This new reconceptualization of identity happened due to global activism and was related to the fact that these were usually people of the same culture or nation mobilizing against a common adversary (accordingly: large corporations / the politics of AKP). Thanks to the Internet though, people had a chance to support the “looting”(1) Turks (and the “99%” of Americans) also elsewhere – in Brazil, Germany or the USA, thus, the shared nationality or culture was not the most important to unite with others oppressed, but the very notion of being oppressed in general.

Just as every festival needs a drama to continue going, so the Turkish government was dosing the protesters with violent police attacks, accusations of looting and blasphemous behaviors such as drinking alcohol in the mosque. Moreover, the Prime Minister decided that the best tactic was to polarize the society by making claims as: “for every 100,000 protesters, I will bring out a million from my party” (Prime Minister’s often used strategy to polarize people by terming that there were “his people” and “the others”) (Haaretz, 2013). This dividing of nation into looters and obedient citizens could have had tragic consequences such as civil war, and yet it could not have happened due to the fact that the majority of society was disinformed about the events via all the major media outlets. The deaths of protestors that have happened during the Gezi “festival” had the effect of reminding to people not to be oppressed by those who are responsible for such incidents.

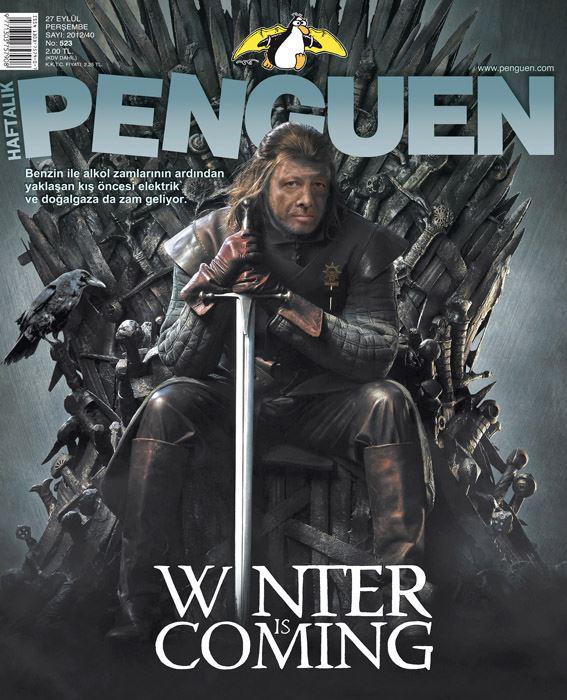

An example of public mockery using the popular culture product

One of the most important aspects of the carnival, mentioned earlier, is parodying. This ability to laugh at oneself happened also during the #Occupy in Boston – Juris mentions about a group of men who dressed in Speedo bathing suits and held signs saying “1% of this SPEEDO is covering 99% of my ?*@!”(2) (263). The humorous approach to the protests was met with others’ approval announced alike in Gezi protests by honking cars, whistles and occasional insults directed at the government. The plentiful of images referring to Gezi protests flooded Facebook and Twitter. Lots of these images stemmed from popular culture using such characters as Lord Vader, Guy Fawkes or slogans from popular TV series like Game of Thrones (saying things as “Tayyip, the winter is coming” as if in the nexus of Arab Spring the winter would come to Turkey). These helped to unload the tension as well as contributing to the jolly mood during the protests. Laughing at the infamous penguins that the CNN TÜRK was broadcasting during the demonstrations rather than taking violent actions against the self-censored media gives the evidence that people were prepared to make peaceful dissent rather than to start a conflict in the already polarized society.

Notwithstanding the violent raids on the protestors’ camps the festival rather passed away on its own. The temporary suspension of the reality could not have been permanent. The festival penetrated people’s consciousness during the protests making them realize that they exist in a bigger community that disagrees with the lawmakers despite their individual and personal views. Although the government made a series of ludicrous accusations such as to seek for international conspiracy or blame the Turkish currency drop on the “looters,” people have become more aware of the “new” propaganda “game” on the government’s side. As Guy Debord said “reality emerges within the spectacle, and the spectacle is real” and “the reciprocal alienation is the essence and support of the existing society.” It is up to the next generations of Turks to decide whether this ideological spectacle will go on or will be shattered and debunked by the social media.

References:

- Abbott, James (2012), “Democracy@internet.org Revisited: analyzing the socio-political impact of the internet and new social media in East Asia”, Third World Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 333-357.

- Althusser, Louis. (1971) Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.

- Bennett, Lance W. (2003), “Communicating Global Activism: Strengths and vulnerabilities of networked politics”, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 143-168.

- Debord, Guy, “The Society of the Spectacle”.

- Freedom House Ranking, web. 19 Dec. 2013, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report-types/freedom-world.

- Grindon, Gavin (2013), “Revolutionary Romanticism: Henri Lefebvre’s Revolution-as-Festival”, Third Text, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 208 – 220.

- Haaretz, “Clashes in Istanbul //$$ Erdogan: For every 100,000 protesters, I will bring out a million from my party”, Jun. 1, 2013, Web. Dec. 19, 2013, http://www.haaretz.com/news/middle-east/1.527188.

- Highmore, Ben, “Henri Lefebvre’s Dialectics of Everyday Life”

- Juris, Jeffrey S. (2012), “Reflection on #Occupy Everywhere: Social media, public sphere, and emerging logics of aggregation”, American Ethnologist, Vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 259-279.

- Hürriyet Daily News, “Female, male students together is against our character: Turkish PM”, Nov. 4, 2013, Web. Dec. 19, 2013 http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/female-male-students-living-together-is-against-our-character-turkish-pm.aspx?PageID=238&NID=57343&NewsCatID=338.

- Lefebvre, Henri (2003), “The Style of the Commune”, Key Writings, Continuum: New York, pp. 188-190.

- Perec, Georges. “Approaches to What?”

- Thompson, Craig. (2007), “A Carnivalesque Approach to the Politics of Consumption (or) Grotesque Realism and the Analytics of the Excretory Economy”, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 611, The Politics of Consumption/The Consumption of Politics, pp. 112-125.

Notes:

- I am referring here to looters in quotation marks due to the fact that the Turkish government itself was denoting them as such (Turkish: çapulcu – marauder, looter).

- The main slogan of the protesters during the #Occupy Wall Street protests was “We are the 99%!”